Biography

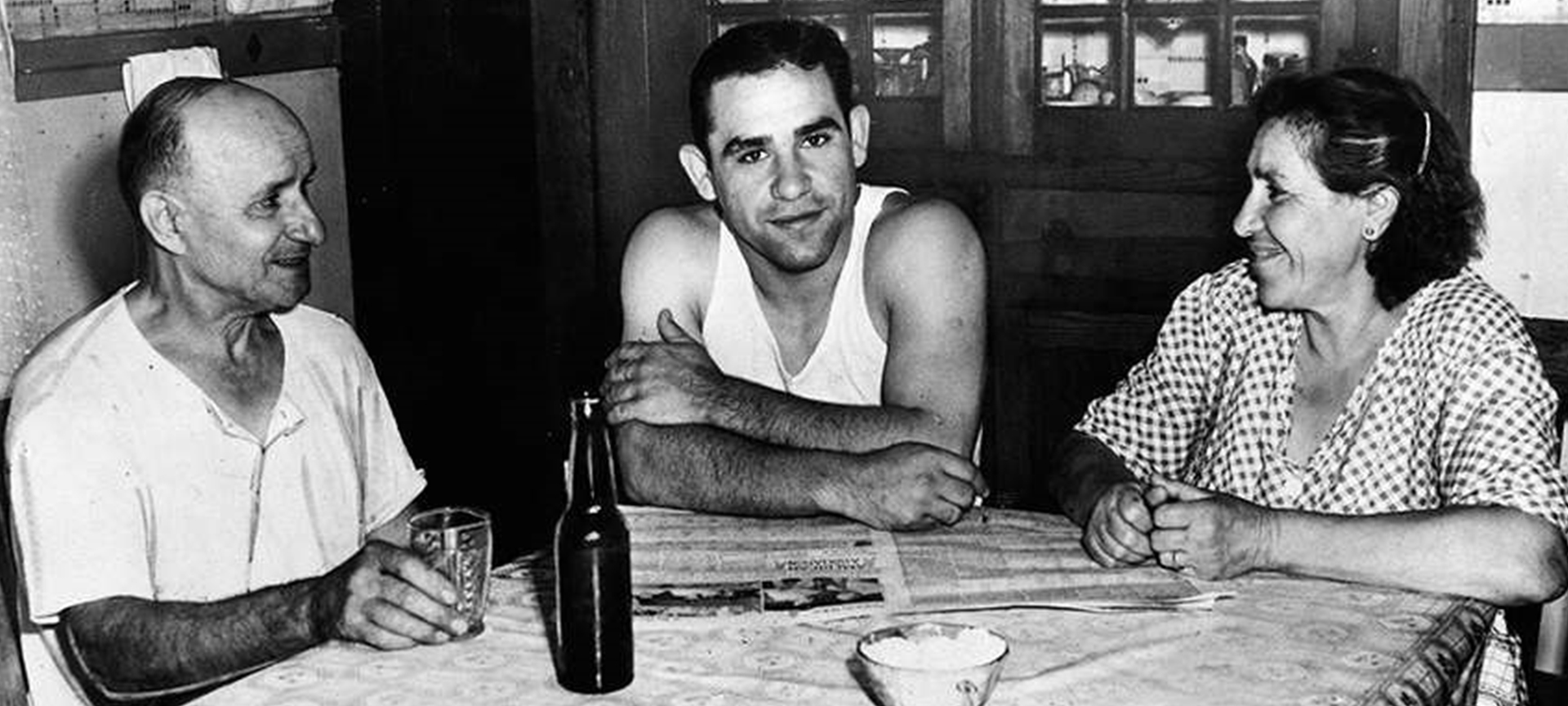

Family Background

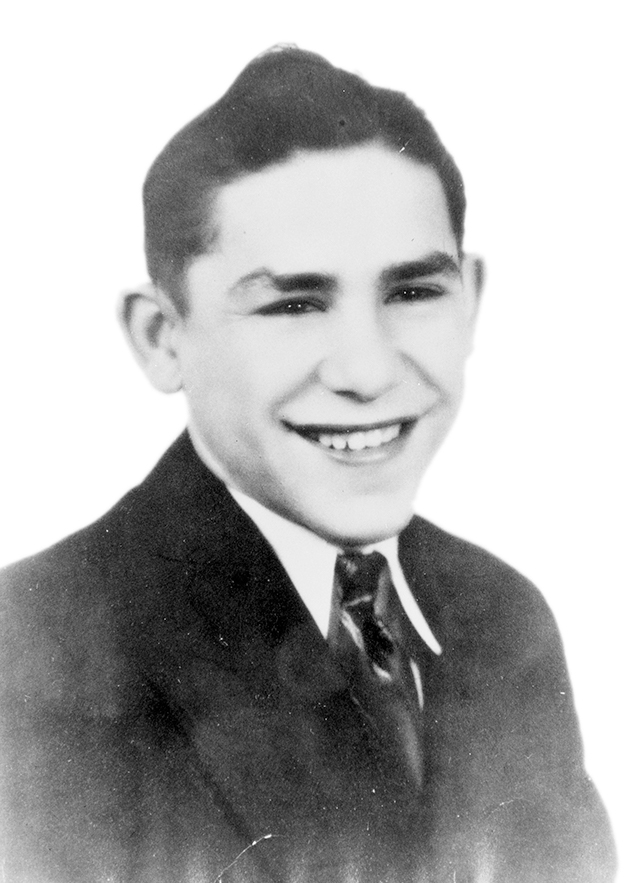

Born into an America that more than one President described as a “nation of immigrants,” Yogi Berra was a first-generation Italian-American who grew up in a St. Louis neighborhood called “The Hill,” where he was surrounded by recent immigrants and raised with a sense of community informed by Italian traditions. Yogi’s father, Pietro, had come to the United States alone in 1909 from Malvaglio, a northern Italian town close to Milan. Temporarily leaving his wife, Paolina, and two firstborn children in Italy, Pietro arrived through Ellis Island alongside thousands of other immigrants from across Europe. After a brief stay in New York City, Pietro settled in St. Louis, his wife and children following him there soon after. Once settled, Pietro and Paolina had three more children, Yogi second among them.

Enter Baseball

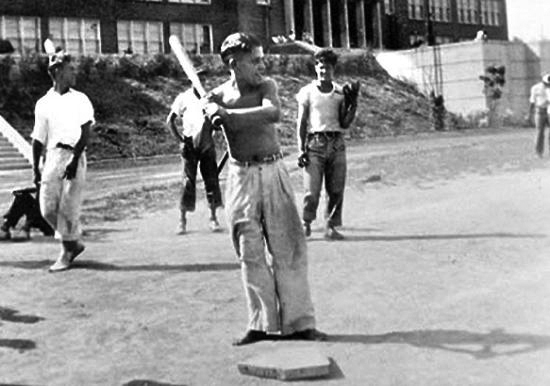

Yogi’s baseball experiences started in his neighborhood, where local children played an informal, “sandlot” version of the game. After leaving school in eighth grade, he graduated to American Legion baseball (for 13- to 19-year-olds), showing himself to have the kind of talent his three older brothers had already demonstrated. Those older brothers had left sports for the workplace at their father’s insistence; Yogi attempted to do both. But baseball regularly interfered with the work.

Yogi’s first glimpse of a possible professional career in the sport came in 1941, at age sixteen, when he joined Joe Garagiola and tried out for their home team, the St. Louis Cardinals. General Manager Branch Rickey offered both young men contracts, but Garagiola was offered a signing bonus of $500, Yogi $250. The difference didn’t sit well with Yogi, and he declined Rickey’s offer. In fact, Rickey’s lesser offer to Yogi was a ploy intended to keep Berra from signing with the Cardinals. Rickey had his own plans to move to Brooklyn, and wanted to save Yogi for the Dodgers. Unfortunately for Rickey, the plan failed. One of Yogi’s American League coaches contacted the New York Yankees on Yogi’s behalf, and the New York team in the Bronx made an offer. It included a $500 signing bonus. Yogi accepted. He would start his professional baseball career with the Yankees, joining the team’s Class B Piedmont League affiliate in Norfolk.

World War II

The Son of Immigrants in the Major Leagues

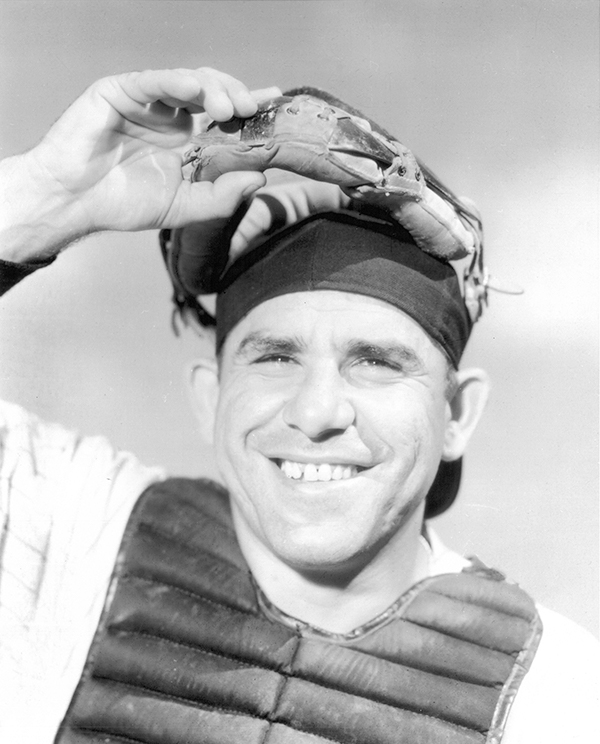

Yogi’s post-war return to baseball saw him joining the Newark Bears, the Yankee’s top minor-league affiliate. In the final weeks of the 1946 season, he was called up to the Major Leagues.He hit a home run against the Philadelphia A’s in his very first game. Not every player sent up from the minors would stay, but Yogi Berra was at the beginning of a long, celebrated career in baseball, first as a player and, later, as a coach and manager. For an Italian-American son of immigrant parents, Yogi’s wartime experiences, together with his entry into the world of Major League baseball, registered as definitively American achievements. It seemed he had situated himself in the heart of an American success story. But this didn’t mean it would all be easy going. As with others born to immigrant families, Yogi knew the cold realities of prejudice. Early in his career, even the Yankee’s manager would casually refer to Yogi as “the Ape.” While the justification for the hurtful epithet was arguably personal, relating to Yogi’s physical appearance, he was not the first Italian-American to be addressed with such slurs—much like those leveled against African-Americans. Indeed, in the period of “The Great Arrival,” when millions of Italians immigrated to the United States, Italians were often categorized as “people of color” and subjected to the harshest realities of prejudice. It was an ugly side of the American experience that Yogi would endure, learn from and, in many ways, transcend, through his innate empathy and sense of justice.

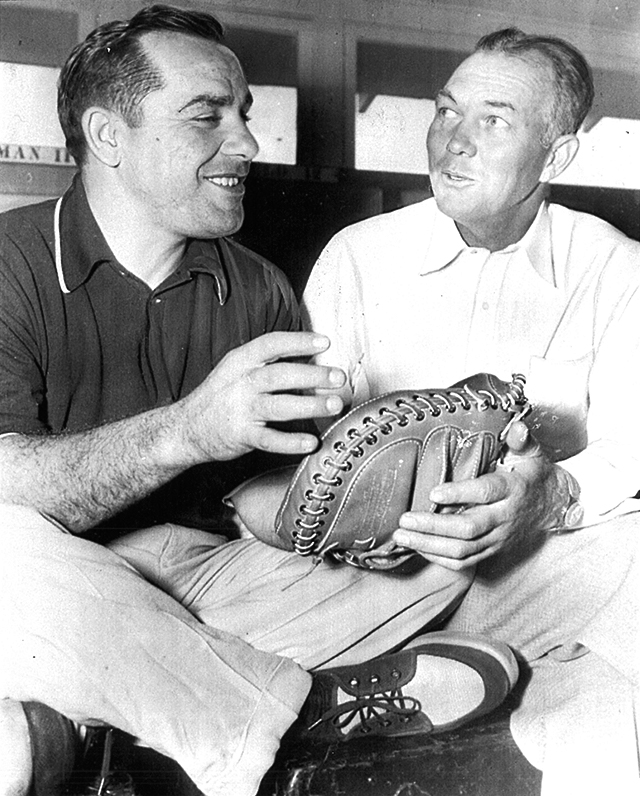

Bill Dickey

The Yankees that Yogi Berra joined late in 1946 included the great Joe DiMaggio. DiMaggio, who would retire in 1951, was nearing the end of an illustrious career. He still held the record for consecutive hits with 56 games in a row, and remained a force on the team. Catcher Bill Dickey would retire after 19 seasons with the Yankees, just as Yogi came onto the team. But Dickey would return as a coach in 1949. Throughout Yogi’s career he credited Dickey, who shared the number 8, with teaching him the art and nuance of being a catcher. Dickey had been a Yankee catcher alongside teammates that included not just DiMaggio, but Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. As coach, he passed a wealth of baseball knowledge onto Yogi. Still, the personnel change that was perhaps the most meaningful to Yogi came with the arrival of Casey Stengel in 1948.

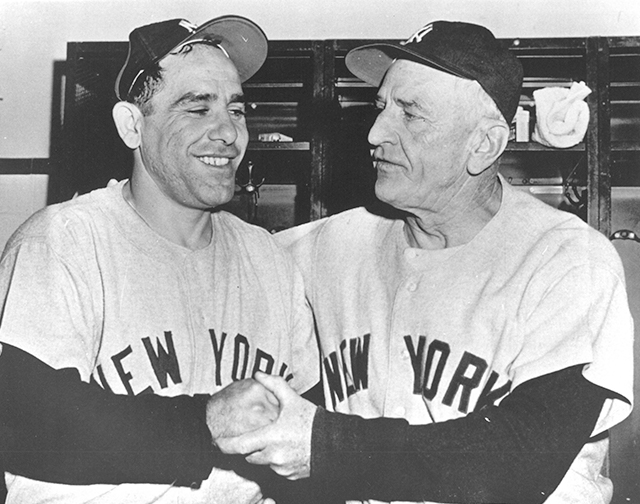

Casey Stengel and Yankee Golden Age

There is little doubt that Stengel’s style with language and word play influenced Yogi’s, and meshed well with the man Yogi was upon arrival at the Yankee camp. When Yogi would later make the transition from player to coach/manager, Stengel remained the model of how that role could be filled to the benefit of a team and the individual players on it.

Carmen

Garagiola finally told Yogi that he needed to ask Carmen on a date, if only so the two baseball players could start going to a restaurant they could afford. Yogi found his courage. His first date with Carmen was a hockey game. The couple married on The Hill in 1949, relocating to New Jersey in 1951, first in Tenafly, then Woodcliff Lake, and finally Montclair, where they lived for more than half a century. They remained happily married for sixty-five years, bringing three children into the world, Larry, Tim, and Dale.

During his time as a Yankee, Yogi built a reputation as a catcher and clutch hitter. As a catcher he once went 148 straight games without making an error. A great ally to pitchers, he caught two no-hitters for Allie Reynolds in 1951, and more significantly, was catcher for Don Larsen’s perfect game in the 1956 World Series, the only perfect game in World Series history. A photo of Yogi leaping into Larsen’s arms in celebration after that game’s final out remains one of baseball’s most iconic images. As a batter, Yogi’s abilities at the plate were also legendary. Despite the power hitters around him, including Joe DiMaggio and later Mickey Mantle, Yogi led the Yankees in RBI’s for seven straight seasons (1949-55). In the batter’s box, he’s remembered for seldom striking out, one of the game’s great bad-ball hitters—a player who swung at bad pitches but just as often connected with the ball, even when pitches were near his eyes or ankles.

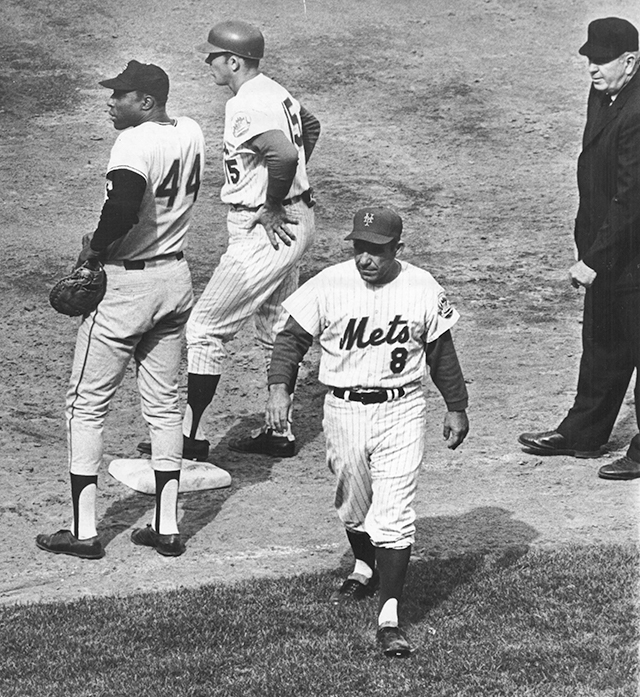

Still in the Game: from Player to Manager and Coach

He led the Mets to a National League Pennant in 1973. After leaving the Mets in 1975, he was back with the Yankees as a coach in 1976, winning the World Series in both 1977 and 1978. In 1984 he was named Yankees manager. After a third place finish in 1984, Yogi was fired just sixteen games into the following season. Owner George Steinbrenner sent a member of his staff to give Yogi the news. Deeply affected by this slight, Yogi vowed not to enter Yankee Stadium again so long as Steinbrenner was team owner. He headed instead for Texas, joining the Houston Astros as a coach in 1986 and remaining there until his retirement in 1992. Still, Yogi’s identity as a NY Yankee remained strong. He and Steinbrenner faced one another again in 1999, meeting at the Yogi Berra Museum & Learning Center where Steinbrenner apologized for his actions and amends were made. Yogi returned triumphantly to Yankee Stadium, and eventually assumed the role of elder statesman for the team, a mentor and friend to many of the younger players. The game was in his heart, and he found ways to share it until the end of his long life.

Most Quotable American

When in 2016 President Barack Obama awarded Yogi with a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom, he adapted a “Yogi-ism” for the occasion, ending his presentation by saying of the great baseball player, “If you can’t imitate him, don’t copy him.” Across generations people have recalled Yogi’s many aphorisms and sayings, making him one of the most quoted Americans in history. In his own way and without ever intending to, Yogi became a literary figure, a man of language. The simplicity of his style appealed to an American audience already attuned to the pithy maxims of such public figures as Mark Twain, Oliver Wendell Holmes and Dorothy Parker. Yet something in Yogi’s humor, turns of phrase and wit made his an even more American voice than others. “When you come to a fork in the road, take it.” “You can observe a lot by watching.” “You should always go to other people’s funerals; otherwise, they won’t come to yours.” The many “Yogi-isms” continue to echo far beyond the world of sports, heard across the whole of American culture.

Lasting Values

Over time Yogi Berra emerged as baseball’s unofficial ambassador and one of the game’s most admired representatives. Well after his official retirement from the game, he remained a beloved presence at spring training and in the Yankees’ clubhouse, an emblem of baseball’s best aspects and living proof of its history. Amidst the accolades and honors, however, Yogi remained a humble hero and a man of the people. As journalist Leonard Koppett wrote: “In the brightest of publicity spotlights, for more than four decades, Yogi remained completely himself—a rarer and more difficult accomplishment than making the Hall of Fame.”

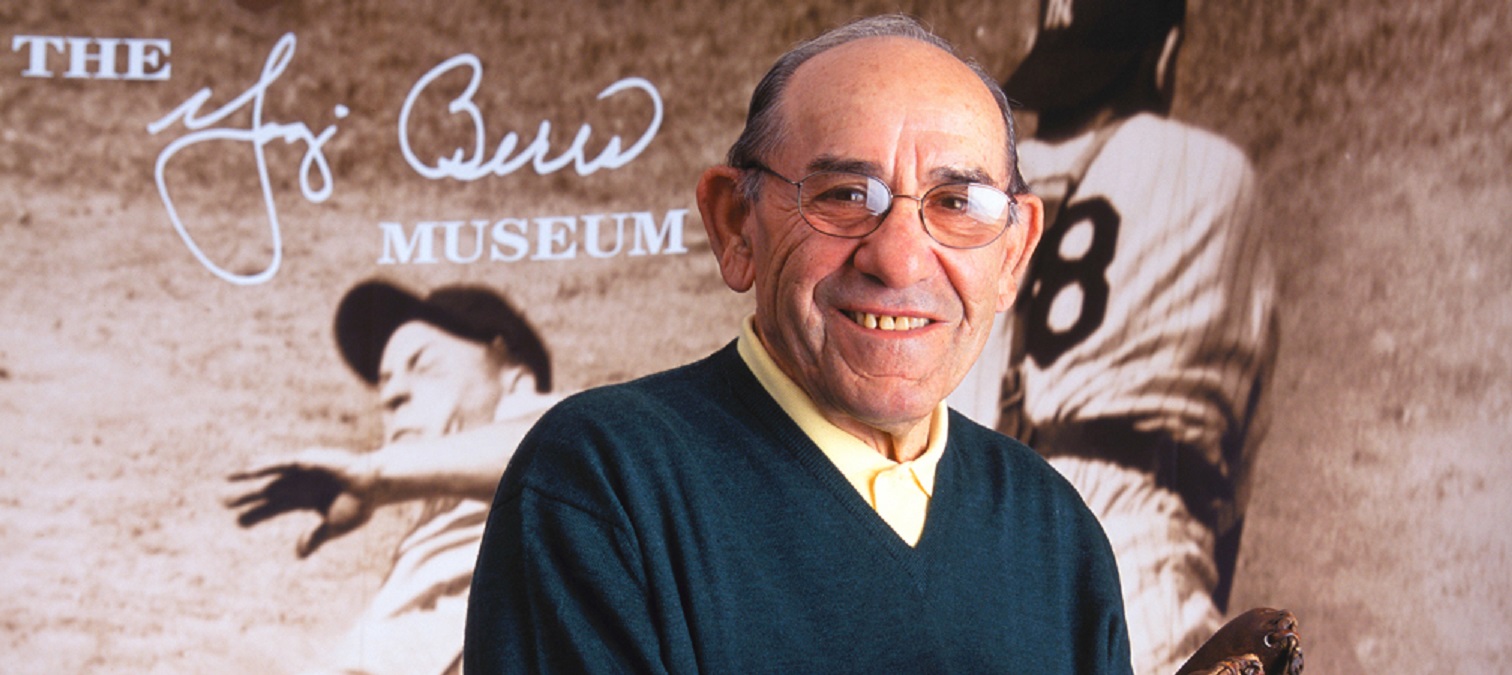

While Yogi’s accomplishments in baseball are the striking centerpiece of his legacy, his integrity and long-held principles are just as crucial. The walls of the Yogi Berra Museum & Learning Center reflect the values that Yogi both espoused and lived by: loyalty, passion, respect, cooperation, wisdom, service, generosity, selflessness and citizenship, among them. Visitors to the Museum will get a sense for them all as they take in Yogi’s story—a story that has, with time, elevated him to the status of national treasure.